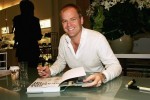

Celebrity chef Bill Granger appears in store to promote and sign copies of his new recipe book Bill Granger Every Day, at David Jones Elizabeth Street store on November 16, 2006 in Sydney, Australia. (Patrick Riviere/Getty Images)

Celebrity chef Bill Granger appears in store to promote and sign copies of his new recipe book Bill Granger Every Day, at David Jones Elizabeth Street store on November 16, 2006 in Sydney, Australia. (Patrick Riviere/Getty Images)

--

Shares

Facebook Twitter Reddit Email

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

On Christmas Day 2023, world-renowned Australian chef and restaurateur Bill Granger died at 54.

Granger owned and operated 19 restaurants across Australia, the U.K., Japan and South Korea. He authored 14 cookbooks, produced several TV shows and was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia.

But his lasting legacy may be his role in making avocado toast a Western culinary staple – and, inadvertently, the viral meme that transformed the open sandwich into a symbol of generational tension.

The practice of spreading avocado on bread has existed for centuries, particularly in Central and South America. Some speculate it dates as far back as the 1500s, when the Spanish settlers brought Western breads to Mexico. But a 2016 Washington Post article pointed to Granger as the first person to put avocado toast on a menu, when he did so at his Sydney café, Bills, in 1993.

I love ordering the occasional avocado toast. But as a sociologist of the internet and social media, I'm most interested in the meme – its origins, how it became a point of contention and how it has ultimately muddied the waters of inequality.

Avocado toast and the American dream

On May 15, 2017, Australian real estate tycoon Tim Gurner said in an interview, "When I was trying to buy my first home, I wasn't buying smashed avocado for $19 and four coffees at $4 each."

Gurner's comments implied that young people were not buying homes at the same rate as older generations due to their poor money management skills – unlike Gurner and his cohort, who understood the value of a buck and the importance of an honest day's work.

No matter that minimal research revealed that Gurner's nearly billion-dollar empire began with financial assistance from his wealthy family. The backlash on the internet was swift and searing, as Gurner became a stand-in for an entire out-of-touch generation who didn't know how easy they had it.

Memes emphasized the fact that baby boomers, in general, had an easier time becoming homeowners compared to millennials, who largely came of age during the post-2008 economic downturn, which forced them to reckon with the crumbling remains of the American dream.

Generational tensions or class tensions?

In their article "A Sociological Analysis of 'OK Boomer,'" sociologists Jason Mueller and John McCollum describe how we're in a period rife with confusions exacerbated by the internet.

They conclude that meme trends like "OK Boomer" – a phrase that Gen Z popularized as an online retort to politicians and reporters who dismissed young people – reflect a world in which generational wars online coexist with class wars offline. The avocado toast meme works in a similar way.

In offline reality, there is some correlation between generations and wealth. But generations are not what ultimately explain class inequality.

Instead, economic sociologists largely agree that a political emphasis on market "freedoms" and the concurrent paring back of programs that distribute resources have led to soaring economic inequality. These include laws that deregulated markets and privatized public spaces, as well as those that scaled back funding for health care, welfare, education and other government services. The policies first emerged under the umbrella of "The Washington Consensus" in the late 20th century.

For example, the Telecommunications Act of 1996, rather than treating emerging internet technology as a public good, ensured the privatization of the internet, paving the way for an online economy that profits off the attention and data of users.

Deregulation has created the conditions for today's economic reality, in which many millennials and Gen Zers must work precarious jobs in the gig economy. They continue to struggle to buy homes and afford rent.

But importantly, many baby boomers face the same economic reality. Millions of them have been forced to delay retirement, particularly if they're from marginalized races and genders.

In other words, the adverse impacts of class inequality leave no generation untouched.

Illusions of separation

So why does it feel like most baby boomers have it so easy?

Cultural theorist Mark Fisher, in his 2009 book "Capitalist Realism," describes this moment in history as one in which "hyperreality" prevails.

The term, coined by French post-modernist Jean Baudrillard in 1981, essentially describes a state in which simulations of reality appear more "real" than reality.

In his book "Simulacra and Simulation," Baudrillard uses the example of Disneyland to describe hyperreality. Many people would rather pay to go to Disneyland – a park built to mimic imaginary places – than travel to national parks, where they can experience nature for free or on the cheap.

The virtual world of the internet – with its own sets of cultural norms, language and memes – is the epitome of hyperreality.

And in the hyperreal world of the internet, as Mueller and McCollum discuss in their article about the "OK Boomer" meme, generational tensions take form.

Memes like avocado toast construct a state of generational conflict in the online world that is real, quite simply, because it feels real.

Algorithms have every incentive to stoke this conflict.

That's because online generational conflicts, along with most social media battles, are immensely profitable. In "Virality: Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks," sociologist Tony Sampson concludes that viral content usually elicits strong emotional reactions.

When users, old and young, are angry with one another, and express that anger in the language of memes, social media platforms like X, formerly known as Twitter, get more engagement and make more money.

Reframing avocado toast

What Sampson finds, though, is that positive feelings also lead to virality.

So perhaps one way to honor Granger is to reclaim the avocado toast meme as an in-joke that nonmillionaires and nonbillionaires of all generations can relate to.

It's about one billionaire's absurd proposition that millennials eating a fleshy fruit on a piece of toast is preventing them from buying homes. It's the billionaire divorced from the struggles of everyday people who's out of touch – not an entire generation of boomers.

The avocado toast meme serves as a reminder that the hyperreal space of the internet distorts an offline reality in which generations share struggles, whether through housing insecurity or delayed retirements – a reality perpetuated by billionaires like Tim Gurner and the economic systems that serve their interests.

Aarushi Bhandari, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Davidson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.